Dalībnieks:Juris789/Smilšu kaste

{{Vielas infokaste

| attēls =

Imatiniba struktūrformula

Imatiniba molekulas datormodelis

| citi nosaukumi = 4-[(4-metilpiperazin-1-il)metil]-N-(4-metil-3-{[4-(piridin-3-il)pirimidin-2-il]amino}fenil)benzamīds | CAS numurs = 152459-95-5 | ķīmiskā formula = C29H31N7O | molmasa = 493,603 }} Imatinibs (starptautiskais nepatentētais nosaukums) jeb gliveks[1] ir tirozīnkināžu inhibitors, kuru izmanto noteiktu veidu ļaundabīgu saslimšanu ārstēšanā, it īpaši Filadelfijas hromosomas pozitīvās (Ph+) hroniskās mieloleikozes (HML) gadījumos.[2] Imatiniba oriģinators ir Novartis, un oriģinālais Imatinibs ir Eiropā pieejams ar preču zīmi Glivec.

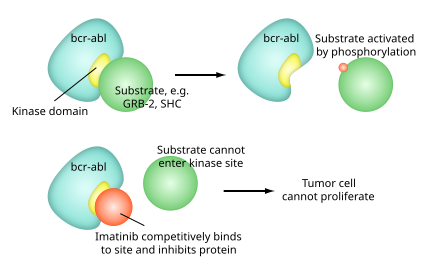

Lai organisma šūnas varētu izdzīvot, tām ir nepieciešams saņemt signālus no citām šūnām ar olbaltumvielu pārnesto signālu kaskādes starpniecību. Daži no šīs kaskādes signāliem tiek ieslēgti, kad signālu nesošajai olbaltumvielai īpaši fermenti (tirozīnkināzes) pievieno fosfāta grupu (notiek olbaltumvielu fosforilēšana). Normālās šūnās tirozīnkināžu aktivitāte tiek precīzi regulēta atbilstoši organisma vajadzībām. Taču Ph+ HML gadījumā viena no tirozīnkināzēm (BCR-Abl) ģenētiskas mutācijas rezultātā ir pārmērīgi aktivizēta un nepārtraukti fosforilē signālus nesošās olbaltumvielas. Imatinibs specifiski bloķē šo kļūdaino tirozīnkināzi un novērš olbaltumvielu pārmērīgo fosforilēšanu. Tā rezultātā mutāciju nesošo audzēja šūnu dalīšanās tiek nomākta un tās iet bojā apoptozes procesā.[3]

Tā kā BCR-Abl tirozīnkināze veidojas tikai mutācijas rezultātā audzēja šūnās, un veselajās šūnās tās nav, tad imatinibs iedarbojas ļoti specifiski - tikai uz audzēja šūnām, kurās ir anomālā Filadelfijas hromosoma.[4] Imatinibs ir viens no pirmajiem šādu, mērķtiecīgi konstruētu, specifisku pretvēža zāļu molekulu piemēriem, un to min kā paraugu tālākajiem pētījumiem ļaundabīgo slimību ārstēšanā.[5]

Lielā mērā pateicoties tieši imatiniba un tam radniecīgu zāļu izgudrošanai, HML pacientu izredzes nodzīvot vairāk kā piecus gadus no diagnozes uzstādīšanas ir palielinājušās no 31% (1993. gadā, pirms imatiniba ieviešanas klīniskajā praksē 2001. gadā) līdz 59% (pacientiem, kuriem diagnoze uzstādīta no 2003. līdz 2009. gadam).[6] Salīdzinot ar agrāk izgudrotajām zālēm, imatiniba blakusefekti parasti nav smagi, un vairumam pacientu ir pieņemama dzīves kvalitāte.[7] Gastrointestinālo stromālo audzēju gadījumā pacientiem, kuri lieto imatinibu, vidējā dzīvildze sasniedz gandrīz 5 gadus, salīdzinot ar 9-20 mēnešiem bez imatiniba.[8]

Imatiniba oriģinators Novartis ir kritizēts par šo zāļu augsto cenu substances patenta darbības periodā (1993-2013), taču līdz ar šī pirmā patenta darbības beigām imatinibu tirgū piedāvā arī citi ražotāji. Latvijas Valsts Zāļu Aģentūrā 2015. gada janvārī ir reģistrētas 19 dažādu ražotāju imatiniba tabletes un kapsulas.[9] Imatiniba dažādus sāļus, kristālus, gatavās zāļu formas un tehnoloģijas aizsargā vēl citi patenti. Indijā šādi papildu patenti ir noraidīti, dodot Indijas ražotājiem un pacientiem lielas un joprojām apstrīdētas priekšrocības.[10]

Izmantošana medicīnā

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Ar imatinibu ārstē hronisko mieloleikozi (HML), gastrointestinālos stromālos audzējus un dažas citas ļaundabīgās saslimšanas.

Hroniskā mieloleikoze

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]ASV Pārtikas un zāļu aģentūra (FDA) 2001. gadā apstiprināja imatinibu kā pirmās rindas zāles Filadelfijas hromosomas pozitīvos HML gadījumos pieaugušajiem un bērniem, tajā skaitā situācijās pēc cilmes šūnu transplantācijas, blastu krīzes gadījumā, kā arī nesen diagnosticētiem pacientiem.[11]

Gastrointestinālie stromālie audzēji

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]FDA 2002. gadā apstiprināja imatiniba lietošanu vēlīno stadiju gastrointestinālo stromālo audzēju gadījumos. Vēlāk, 2012. gadā imatinibu apstiprināja lietošanai pēc KIT-pozitīvu audzēju izoperēšanas, lai palīdzētu novērst recidīvus.[12] Šīs zāles ir apstiprinātas lietošanai arī neoperējamu KIT-pozitīvu gastrointestinālo stromālo audzēju gadījumos.[11]

Citas indikācijas

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]FDA atļauj imatinibu lietot pieaugušajiem ar relapsējušu vai rezistentu Filadelfijas hromosomas pozitīvo akūto limfoblastisko leikozi (Ph+ ALL), ar trombocītu augšanas faktora receptora gēnu pārgrupēšanos saistītām mielodisplastiskām/mieloproliferācijas slimībām, agresīvu sistēmisku mastocitozi bez / ar nezināmu D816V c-KIT mutāciju, hipereozinofīlo sindromu (HES) un/vai hronisku eozinofīlo leikozi (HEL), kam ir FIP1L1-PDGFRα hibrīdā kināze (CHIC2 alleles delēcija) vai FIP1L1-PDGFRα hibrīdās kināzes negatīva, vai nezināma, neoperējama, recidivējoša un/vai metastazējoša dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.[13] Savukārt 2013. gada 25. janvārī imatinibu apstiprināja lietošanai bērniem ar Ph+ ALL.[14]

Imatiniba spēja bloķēt c-KIT tirozīnkināzi ir devusi cerību, ka ar imatinibu varētu ārstēt progresējošu pleksiformo neirofibromu, kura ir saistīta ar I tipa neirofibromatozi.[15][16][17][18]

Eksperimentālās terapijas

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Vienā pētījumā ir konstatēts, ka imatiniba mezilāts ir efektīvas zāles pacientiem ar sistēmisko mastocitozi, tajā skaitā gadījumos ar c-KIT D816V mutāciju.[19] Tomēr ir arī zināms, ka imatinibs saistās ar tirozīnkināzēm to neaktīvajā konfigurācijā, bet c-KIT D816V mutācija dod pastāvīgi aktīvu tirozīnkināzi, tāpēc imatinibs nevar inhibēt c-KIT D816V mutanta tirozīnkināzes aktivitāti. Pieredze rāda, ka pacientiem ar šo mutāciju imatinibs ir ievērojami mazāk efektīvs, un gandrīz 90% no mastocitozes pacientiem ir šī mutācija.

Imatinibam varētu būt arī nozīme pulmonārās hipertensijas ārstēšanā. Pētījumi rāda, ka imatinibs daudzu slimību gadījumos, tajā skaitā protopulmonārās hipertensijas pacientiem samazina gludās muskulatūras hipertrofiju un plaušu asinsvadu hiperplāziju.[20] Sistēmiskās sklerozes pacientiem imatinibs ir izmēģināts kā līdzeklis, lai palēninātu plaušu fibrozi. Laboratorijas apstākļos imatinibu izmanto kā līdzekli, kurš nomāc trombocītu augšanas faktora (PDGF) iedarbību, inhibējot tā receptoru (PDGF-Rβ). Viens no šīs iedarbības rezultātiem ir aterosklerozes aizkavēšana normālās pelēs[21], vai arī pelēs ar diabētu.[22]

Mouse animal studies have suggested that imatinib and related drugs may be useful in treating smallpox, should an outbreak ever occur.[23]

In vitro studies identified that a modified version of imatinib can bind to gamma-secretase activating protein (GSAP), which selectively increases the production and accumulation of neurotoxic beta-amyloid plaques. This suggests molecules that target at GSAP and are able to cross blood–brain barrier are potential therapeutic agents for treating Alzheimer's disease.[24] Another study suggests that imatinib may not need to cross the blood–brain barrier to be effective at treating Alzheimer's, as the research indicates the production of beta-amyloid may begin in the liver. Tests on mice indicate that imatinib is effective at reducing beta-amyloid in the brain.[25] It is not known whether reduction of beta-amyloid is a feasible way of treating Alzheimer's, as an anti-beta-amyloid vaccine has been shown to clear the brain of plaques without having any effect on Alzheimer symptoms.[26]

A formulation of imatinib with a cyclodextrin (Captisol) as a carrier to overcome the blood–brain barrier is also currently considered as an experimental drug for lowering and reversing opioid tolerance. Imatinib has shown reversal of tolerance in rats.[27] Imatinib is an experimental drug in the treatment of desmoid tumor or aggressive fibromatosis.

Contraindications and cautions

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]The only known contraindication to imatinib is hypersensitivity to imatinib.[28] Cautions include:[29]

- Hepatic impairment, such as in the elderly.

- Risk of severe CHF or left ventricular dysfunction, especially in patients with comorbidities

- Pregnancy, risk of embryo-foetal toxicity.

- Risk of fluid retention

- Risk of growth stunting in children or adolescents

Adverse effects

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]

The most common side effects include feeling sick (nausea), diarrhea, headaches, leg aches/cramps, fluid retention, visual disturbances, itchy rash, lowered resistance to infection, bruising or bleeding, loss of appetite;[30] weight gain, reduced number of blood cells (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia), and edema.[31]

Severe congestive cardiac failure is an uncommon but recognized side effect of imatinib and mice treated with large doses of imatinib show toxic damage to their myocardium.[32]

If imatinib is used in prepubescent children, it can delay normal growth, although a proportion will experience catch-up growth during puberty.[33]

Interactions

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Its use is advised against in patients on strong CYP3A4 inhibitors such as clarithromycin, chloramphenicol, ketoconazole, ritonavir and nefazodone due to its reliance on CYP3A4 for metabolism.[29] Likewise it is a CYP3A4, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 inhibitor and hence concurrent treatment with substrates of any of these enzymes may increase plasma concentrations of said drugs.[29]

Overdose

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Medical experience with imatinib overdose is limited and treatment is purely supportive.[34] Dialysis is unlikely to be helpful seeing how highly plasma protein-bound imatinib is.[34] Symptoms of minor overdose include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Rash

- Erythema

- Oedema

- Swelling

- Fatigue

- Muscle spasms

- Thrombocytopenia

- Pancytopenia

- Abdominal pain

- Headache

- Decreased appetite

Symptoms of moderate overdose include:[34]

- Weakness

- Myalgia

- Increased CPK

- Increased bilirubin

- Gastrointestinal pain

Whereas symptoms of one single severe overdose include:[34]

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Pyrexia

- Facial swelling

- Neutrophil count decreased

- Increased transaminases

Mechanism of action

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]

Veidne:Infobox drug mechanism Imatinib is a 2-phenyl amino pyrimidine derivative that functions as a specific inhibitor of a number of tyrosine kinase enzymes. It occupies the TK active site, leading to a decrease in activity.

There are a large number of TK enzymes in the body, including the insulin receptor. Imatinib is specific for the TK domain inabl (the Abelson proto-oncogene), c-kit and PDGF-R (platelet-derived growth factorreceptor).

In chronic myelogenous leukemia, the Philadelphia chromosome leads to a fusion protein of abl with bcr (breakpoint cluster region), termed bcr-abl. As this is now a constitutively active tyrosine kinase, imatinib is used to decrease bcr-abl activity.

The active sites of tyrosine kinases each have a binding site for ATP. The enzymatic activity catalyzed by a tyrosine kinase is the transfer of the terminal phosphate from ATP to tyrosine residues on its substrates, a process known as protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Imatinib works by binding close to the ATP binding site of bcr-abl, locking it in a closed or self-inhibited conformation, and therefore inhibiting the enzyme activity of the protein semi-competitively.[35] This fact explains why many BCR-ABL mutations can cause resistance to imatinib by shifting its equilibrium toward the open or active conformation.[36]

Imatinib is quite selective for bcr-abl – it does also inhibit other targets mentioned above (c-kit and PDGF-R), but no other known tyrosine kinases. Imatinib also inhibits the abl protein of non-cancer cells but cells normally have additional redundant tyrosine kinases which allow them to continue to function even if abl tyrosine kinase is inhibited. Some tumor cells, however, have a dependence on bcr-abl.[37] Inhibition of the bcr-abl tyrosine kinase also stimulates its entry in to the nucleus, where it is unable to perform any of its normal anti-apoptopic functions.[38]

The Bcr-Abl pathway has many downstream pathways including the Ras/MapK pathway, which leads to increased proliferation due to increased growth factor-independent cell growth. It also affects the Src/Pax/Fak/Rac pathway. This affects the cytoskeleton, which leads to increased cell motility and decreased adhesion. The PI/PI3K/AKT/BCL-2 pathway is also affected. BCL-2 is responsible for keeping the mitochondria stable; this suppresses cell death by apoptosis and increases survival. The last pathway that Bcr-Abl affects is the JAK/STAT pathway, which is responsible for proliferation.[39]

Pharmacokinetics

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Imatinib is rapidly absorbed when given by mouth, and is highly bioavailable: 98% of an oral dose reaches the bloodstream. Metabolism of imatinib occurs in the liver and is mediated by several isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. The main metabolite, N-demethylated piperazine derivative, is also active. The major route of elimination is in the bile and feces; only a small portion of the drug is excreted in the urine. Most of imatinib is eliminated as metabolites; only 25% is eliminated unchanged. The half-lives of imatinib and its main metabolite are 18 and 40 hours, respectively. It blocks the activity of Abelson cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase (ABL), c-Kit and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). As an inhibitor of PDGFR, imatinib mesylate appears to have utility in the treatment of a variety of dermatological diseases. Imatinib has been reported to be an effective treatment for FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha+ mast cell disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.[40]

Interactions

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Since imatinib is mainly metabolised via the liver enzyme CYP3A4, substances influencing the activity of this enzyme change the plasma concentration of the drug. An example of a drug that increases imatinib activity and therefore side effects by blocking CYP3A4 is ketoconazole. The same could be true of itraconazole, clarithromycin, grapefruit juice, among others. Conversely, CYP3A4 inductors like rifampicin and St. John's Wort reduce the drug's activity, risking therapy failure. Imatinib also acts as an inhibitor of CYP3A4, 2C9 and 2D6, increasing the plasma concentrations of a number of other drugs like simvastatin, ciclosporin, pimozide, warfarin, metoprolol, and possibly paracetamol. The drug also reduces plasma levels of levothyroxin via an unknown mechanism.[31]

As with other immunosuppressants, application of live vaccines is contraindicated because the microorganisms in the vaccine could multiply and infect the patient. Inactivated and toxoid vaccines do not hold this risk, but may not be effective under imatinib therapy.[41]

History

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Imatinib was invented in the late 1990s by scientists at Ciba-Geigy (which merged with Sandoz in 1996 to become Novartis), in a team led by biochemist Nicholas Lydon and that included Elisabeth Buchdunger and Jürg Zimmerman[42] and its use to treat CML was driven by oncologist Brian Druker of Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU).[43] Other major contributions to imatinib development were made by Carlo Gambacorti-Passerini, a physician scientist and hematologist at University of Milano Bicocca, Italy, John Goldman at Hammersmith Hospital in London, UK, and later on by Charles Sawyers of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.[44] Druker led the clinical trials confirming its efficacy in CML.[45]

Imatinib was developed by rational drug design. After the Philadelphia chromosome mutation and hyperactive bcr-abl protein were discovered, the investigators screened chemical libraries to find a drug that would inhibit that protein. With high-throughput screening, they identified 2-phenylaminopyrimidine. This lead compound was then tested and modified by the introduction of methyl and benzamide groups to give it enhanced binding properties, resulting in imatinib.[46]

A Swiss patent application was filed on imanitib and various salts on in April 1992, which was then filed in the EU, the US, and other countries in March and April 1993.[47][48] and in 1996 United States and European patent offices issued patents listing Jürg Zimmerman as the inventor.[47][49]

In July 1997, Novartis filed a new patent application in Switzerland on the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate (the mesylatesalt of imatinib). The "beta crystalline form" of the molecule is a specific polymorph of imatinib mesylate; a specific way that the individual molecules pack together to form a solid. This is the actual form of the drug sold as Gleevec/Glivec; a salt (imatinib mesylate) as opposed to a free base, and the beta crystalline form as opposed to the alpha or other form.[50]:3 and 4 In 1998, Novartis filed international patent applications claiming priority to the 1997 filing.[51][52] A United States patent was granted in 2005.[53]

Both Novartis US patents mentioned here – the one on the freebase form of imatinib, and the one on the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate – are listed by Novartis along with others in the FDA's Orange Book entry for Gleevec.[54]

The first clinical trial of Gleevec took place in 1998 and the drug received FDA approval in May 2001, only two and a half months after the new drug application was submitted.[42][55] On the same month it made the cover of TIME magazine as a "bullet" to be used against cancer. Druker, Lydon and Sawyers received the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award in 2009 for "converting a fatal cancer into a manageable chronic condition".[44]

During the FDA review, the tradename of the drug for the US market was changed from "Glivec" to "Gleevec" at the request of the FDA, to avoid confusion with Glyset, a diabetes drug.[56][57][58]

Costs

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]

In 2013, more than 100 cancer specialists published a letter in Blood saying that the prices of many new cancer drugs, including imatinib, are so high that U.S. patients couldn't afford them, and that the level of prices, and profits, was so high as to be immoral.[59][60] They stated that in 2001, imatinib was priced at $30,000 a year, which was based on the price of interferon, then the standard treatment, and that at this price Novartis would have recouped its initial development costs in two years. They stated that after unexpectedly becoming a blockbuster, Novartis increased the price to $92,000 per year in 2012, with annual revenues of $4.7 billion. Other doctors have complained about the cost.[61][62][63]

A 2012 economic analysis funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and estimated that the discovery and development and imatinib and related drugs had created $143 billion in societal value at a cost to consumers of approximately $14 billion. The $143 billion figure was based on an estimated 7.5 to 17.5 year survival advantage conferred by imatinib treatment, and included the value of ongoing benefits to society after the imatinib patent expiration.[64]

Prices for a 100 mg pill of Gleevec internationally range from $20 to $30,[65] although generic imatinib is cheaper, as low as $2 per pill.[66]

Patent litigation in India

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Novartis fought a seven year, controversial battle to patent Gleevec in India, and took the case all the way to the Indian Supreme Court. The patent application at the center of the case was filed by Novartis in India in 1998, after India had agreed to enter the World Trade Organization and to abide by worldwide intellectual property standards under the TRIPS agreement. As part of this agreement, India made changes to its patent law; the biggest of which was that prior to these changes, patents on products were not allowed, while afterwards they were, albeit with restrictions. These changes came into effect in 2005, so Novartis' patent application waited in a "mailbox" with others until then, under procedures that India instituted to manage the transition. India also passed certain amendments to its patent law in 2005, just before the laws came into effect.[67]

The patent application[52][68] claimed the final form of Gleevec (the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate).[69]:3 In 1993, during the time India did not allow patents on products, Novartis had patented imatinib, with salts vaguely specified, in many countries but could not patent it in India.[47][49] The key differences between the two patent applications, were that 1998 patent application specified the counterion (Gleevec is a specific salt – imatinib mesylate) while the 1993 patent application did not claim any specific salts nor did it mention mesylate, and the 1998 patent application specified the solid form of Gleevec – the way the individual molecules are packed together into a solid when the drug itself is manufactured (this is separate from processes by which the drug itself is formulated into pills or capsules) – while the 1993 patent application did not. The solid form of imatinib mesylate in Gleevec is beta crystalline.[70]

As provided under the TRIPS agreement, Novartis applied for Exclusive Marketing Rights (EMR) for Gleevec from the Indian Patent Office and the EMR was granted in November 2003.[71] Novartis made use of the EMR to obtain orders against some generic manufacturers who had already launched Gleevec in India.[72][73]

When examination of Novartis' patent application began in 2005, it came under immediate attack from oppositions initiated by generic companies that were already selling Gleevec in India and by advocacy groups. The application was rejected by the patent office and by an appeal board. The key basis for the rejection was the part of Indian patent law that was created by amendment in 2005, describing the patentability of new uses for known drugs and modifications of known drugs. That section, Paragraph 3d, specified that such inventions are patentable only if "they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy."[72][74] At one point, Novartis went to court to try to invalidate Paragraph 3d; it argued that the provision was unconstitutionally vague and that it violated TRIPS. Novartis lost that case and did not appeal.[75] Novartis did appeal the rejection by the patent office to India's Supreme Court, which took the case.

The Supreme Court case hinged on the interpretation of Paragraph 3d. The Supreme Court issued its decision in 2013, ruling that the substance that Novartis sought to patent was indeed a modification of a known drug (the raw form of imatinib, which was publicly disclosed in the 1993 patent application and in scientific articles), that Novartis did not present evidence of a difference in therapeutic efficacy between the final form of Gleevec and the raw form of imatinib, and that therefore the patent application was properly rejected by the patent office and lower courts.[76]

See also

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]- Bcr-Abl tyrosine-kinase inhibitor

- History of cancer chemotherapy

- Gefitinib (Iressa®)

- Dasatinib (BMS-354825)

- Doramapimod • BIRB-796

References

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]- ↑ Indulis Purviņš, Santa Purviņa. Praktiskā farmakoloģija. R:, Zāļu infocentrs, 2011, 349. lpp. ISBN 978-9984-854-20-5

- ↑ Novartis Pharma AG. Gleevec® (imatinib mesylate) tablets prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2006 Sep. Anon. Drugs of choice for cancer. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2003; 1:41–52

- ↑ Goldman JM, Melo JV (October 2003). "Chronic myeloid leukemia – advances in biology and new approaches to treatment". N. Engl. J. Med. 349 (15): 1451–64.

- ↑ Fausel, C. Targeted chronic myeloid leukemia therapy: Seeking a cure. Am J Health Syst Pharm 64, S9-15 (2007).

- ↑ Stegmeier F, Warmuth M, Sellers WR, Dorsch M (May 2010). "Targeted cancer therapies in the twenty-first century: lessons from imatinib". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 87 (5): 543–52.

- ↑ «Leukemia - Chronic Myeloid - CML: Statistics». Teksts " Cancer.Net" ignorēts

- ↑ «leukaemialymphomaresearch.org.uk».

- ↑ De Giorgi U, Verweij J (March 2005). "Imatinib and gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Where do we go from here?". Mol. Cancer Ther. 4 (3): 495–501.

- ↑ «Latvijas Zāļu Valsts Aģentūras informācija par reģistrētiem imatiniba ražotājiem».

- ↑ «Novartis fails to patent Glivec (Gleevec) in India».

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 «FDA Highlights and Prescribing Information for Gleevec(imatinib mesylate)».

- ↑ «Prolonged Use of Imatinib in GIST Patients Leads to New FDA Approval».

- ↑ rl=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021588s024lbl.pdf}}

- ↑ «FDA approves Gleevec for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia». FDA News Release. US Food and Drug Administration. 2013. gada 25. janvāris. Skatīts: 2013. gada 3. aprīlis.

- ↑ Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, Zhu Y, Yuan J, Li X, Yang X, Knowles S, Horn W, Li Y, Zhang S, Yang Y, Vakili ST, Yu M, Burns D, Robertson K, Hutchins G, Parada LF, Clapp DW (October 2008). "Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/--and c-kit-dependent bone marrow". Cell 135 (3): 437–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.041. PMC 2788814. PMID 18984156. Kopsavilkums – Science Daily.

- ↑ «Gleevec NF1 Trial». Nfcure.org. Skatīts: 2013-04-03.

- ↑ «GIST in Neurofibromatosis 1». Gistsupport.org. 2010-05-14. Skatīts: 2013-04-03.

- ↑ «"Pilot Study of Gleevec/Imatinib Mesylate (STI-571, NSC 716051) in Neurofibromatosis (NF1) Patient With Plexiform Neurofibromas (0908-09)" (Suspended)». Clinicaltrials.gov. Skatīts: 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Droogendijk HJ, Kluin-Nelemans HJ, van Doormaal JJ, Oranje AP, van de Loosdrecht AA, van Daele PL (July 2006). "Imatinib mesylate in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis: a phase II trial". Cancer 107 (2): 345–51. doi:10.1002/cncr.21996. PMID 16779792.

- ↑ Tapper EB, Knowles D, Heffron T, Lawrence EC, Csete M (June 2009). "Portopulmonary hypertension: imatinib as a novel treatment and the Emory experience with this condition". Transplant. Proc. 41 (5): 1969–71. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.100. PMID 19545770.

- ↑ Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J (April 2003). "LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis". Science 300 (5617): 329–32. doi:10.1126/science.1082095. PMID 12690199.

- ↑ Lassila M, Allen TJ, Cao Z, Thallas V, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Candido R, Cooper ME (May 2004). "Imatinib attenuates diabetes-associated atherosclerosis". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24 (5): 935–42. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000124105.39900.db. PMID 14988091.

- ↑ Reeves PM, Bommarius B, Lebeis S, McNulty S, Christensen J, Swimm A, Chahroudi A, Chavan R, Feinberg MB, Veach D, Bornmann W, Sherman M, Kalman D (July 2005). "Disabling poxvirus pathogenesis by inhibition of Abl-family tyrosine kinases". Nat. Med. 11 (7): 731–9. doi:10.1038/nm1265. PMID 15980865.

- ↑ He G, Luo W, Li P, Remmers C, Netzer WJ, Hendrick J, Bettayeb K, Flajolet M, Gorelick F, Wennogle LP, Greengard P (September 2010). "Gamma-secretase activating protein is a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease". Nature 467 (7311): 95–8. doi:10.1038/nature09325. PMC 2936959. PMID 20811458.

- ↑ «Alzheimer's may start in liver – Health – Alzheimer's Disease | NBC News». MSNBC. Skatīts: 2013-01-06.

- ↑ Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, Jones RW, Bullock R, Love S, Neal JW, Zotova E, Nicoll JA (July 2008). "Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial". Lancet 372 (9634): 216–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. PMID 18640458.

- ↑ Eliminating Morphine Tolerance – Reformulated Imatinib 23 Feb 2012, 5:00 PST

- ↑ «GLIVEC Tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)». electronic Medicines Compendium. Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd.

- ↑ 29,0 29,1 29,2 «Gleevec (imatinib) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more». Medscape Reference. WebMD. Skatīts: 2014. gada 24. janvāris.

- ↑ «Imatinib». Macmillan Cancer Support. Skatīts: 2012. gada 26. decembris.

- ↑ 31,0 31,1 Haberfeld, H (redaktors). Austria-Codex (German) (2009/2010 izd.). Vienna : Österreichischer Apothekerverlag, 2009. ISBN 3-85200-196-X.

- ↑ Kerkelä R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, Walters B, Shevtsov S, Pesant S, Clubb FJ, Rosenzweig A, Salomon RN, Van Etten RA, Alroy J, Durand JB, Force T (August 2006). "Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate". Nat. Med. 12 (8): 908–16. doi:10.1038/nm1446. PMID 16862153.

- ↑ Shima H, Tokuyama M, Tanizawa A, Tono C, Hamamoto K, Muramatsu H, Watanabe A, Hotta N, Ito M, Kurosawa H, Kato K, Tsurusawa M, Horibe K, Shimada H (October 2011). "Distinct impact of imatinib on growth at prepubertal and pubertal ages of children with chronic myeloid leukemia". J. Pediatr. 159 (4): 676–81. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.046. PMID 21592517.

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 34,2 34,3 «GLIVEC (imatinib)» (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd. 2013. gada 21. augusts. Skatīts: 2014. gada 24. janvāris.

- ↑ Takimoto CH, Calvo E. "Principles of Oncologic Pharmacotherapy" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds)Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 11 ed. 2008.

- ↑ Gambacorti-Passerini CB, Gunby RH, Piazza R, Galietta A, Rostagno R, Scapozza L (February 2003). "Molecular mechanisms of resistance to imatinib in Philadelphia-chromosome-positive leukaemias". Lancet Oncol. 4 (2): 75–85. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(03)00979-3. PMID 12573349.

- ↑ Deininger MW, Druker BJ (September 2003). "Specific targeted therapy of chronic myelogenous leukemia with imatinib". Pharmacol. Rev. 55 (3): 401–23. doi:10.1124/pr.55.3.4. PMID 12869662.

- ↑ Vigneri P, Wang JY (February 2001). "Induction of apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells through nuclear entrapment of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase". Nat. Med. 7 (2): 228–34. doi:10.1038/84683. PMID 11175855.

- ↑ Weisberg E, Manley PW, Cowan-Jacob SW, Hochhaus A, Griffin JD (May 2007). "Second generation inhibitors of BCR-ABL for the treatment of imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukaemia". Nature Reviews Cancer 7 (5): 345–56. doi:10.1038/nrc2126. PMID 17457302.

- ↑ Scheinfeld N, Schienfeld N (February 2006). "A comprehensive review of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) for dermatological diseases". J Drugs Dermatol 5 (2): 117–22. PMID 16485879.

- ↑ Klopp, T (redaktors). Arzneimittel-Interaktionen (German) (2010/2011 izd.). Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Pharmazeutische Information, 2010. ISBN 978-3-85200-207-1.

- ↑ 42,0 42,1 Staff, Innovation.org (a project of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America)The Story of Gleevec

- ↑ Claudia Dreifus for the New York Times. November 2, 2009 Researcher Behind the Drug Gleevec

- ↑ 44,0 44,1 A Conversation With Brian J. Druker, M.D., Researcher Behind the Drug Gleevec by Claudia Dreifus, The New York Times, 2 November 2009

- ↑ Gambacorti-Passerini C (2008). "Part I: Milestones in personalised medicine—imatinib". Lancet Oncology 9 (600): 600. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70152-9. PMID 18510992.

- ↑ Druker BJ, Lydon NB (January 2000). "Lessons learned from the development of an abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myelogenous leukemia". J. Clin. Invest. 105 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1172/JCI9083. PMC 382593. PMID 10619854.

- ↑ 47,0 47,1 47,2 ASV patents Nr. 5,521,184

- ↑ «Imatinib Patent Family». Espacenet. 1996. Skatīts: 2014-07-23.

- ↑ 49,0 49,1 EP 0564409

- ↑ Staff, European Medicines Agency, 2004.EMEA Scientific Discussion of Glivec

- ↑ Note: The Indian patent application, which became the subject of litigation in India that gathered a lot of press, does not appear to be publicly available. However according to documents produced in the course of that litigation (page 27), "The Appellant’s application under the PCT was substantially on the same invention as had been made in India."

- ↑ 52,0 52,1 WO 9903854 Kļūda atsaucē: nederīga

<ref>iezīme; nosaukums "PCT" definēts vairākas reizes ar dažādu saturu - ↑ ASV patents Nr. 6,894,051

- ↑ FDA Orange Book; Patent and Exclusivity Search Results from query on Appl No 021588 Product 001 in the OB_Rx list.

- ↑ Novartis press release, May 10, 2001. FDA approves Novartis' unique cancer medication Glivec®

- ↑ Cohen MH et al. Approval Summary for Imatinib Mesylate Capsules in the Treatment of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Clin Cancer Res May 2002 8; 935

- ↑ Margot J. Fromer for Oncology Times. December 2002. What’s in a Name? Quite a Lot When It Comes to Marketing & Selling New Cancer Drugs

- ↑ Novartis Press Release. April 30, 2001 Novartis Oncology Changes Trade Name of Investigational Agent Glivec(TM) to Gleevec(TM) in the United States

- ↑ The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: from the perspective of a large group of CML experts.. 121. May 2013. 4439–42. lpp. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-03-490003. PMID 23620577.

- ↑ Andrew Pollack for the New York Times, April 25, 2013 Doctors Denounce Cancer Drug Prices of $100,000 a Year

- ↑ Schiffer CA (July 2007). "BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myelogenous leukemia". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (3): 258–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMct071828. PMID 17634461.

- ↑ As Pills Treat Cancer, Insurance Lags Behind, By ANDREW POLLACK, New York Times, 14 April 2009

- ↑ Living With a Formerly fatal Blood Cancer, By JANE E. BRODY, New York Times, 18 January 2010

- ↑ Yin W, Penrod JR, Maclean R, Lakdawalla DN, Philipson T (November 2012). "Value of survival gains in chronic myeloid leukemia". Am J Manag Care 18 (11 Suppl): S257–64. PMID 23327457.

- ↑ Patented Medicine Review Board (Canada). Report on New Patented Drugs – Gleevec.

- ↑ «pharmacychecker.com». pharmacychecker.com. Skatīts: 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Gardiner Harris and Katie Thomas for the New York Times. April 1, 2013 Top court in India rejects Novartis drug patent

- ↑ Note: The Indian patent application No.1602/MAS/1998 does not appear to be publicly available. However according to the decision of the IPAB on 26 June 2009 (page 27) discussed below, "The Appellant’s application under the PCT was substantially on the same invention as had been made in India."

- ↑ Staff, European Medicines Agency, 2004. EMEA Scientific Discussion of Glivec

- ↑ Indian Supreme Court Decision paragraphs 5–6

- ↑ Novartis v UoI, para 8–9

- ↑ 72,0 72,1 Shamnad Basheer for Spicy IP March 11, 2006 First Mailbox Opposition (Gleevec) Decided in India

- ↑ R. Jai Krishna and Jeanne Whalen for the Wall Street Journal. April 1, 2013 Novartis Loses Glivec Patent Battle in India

- ↑ Intellectual Property Appellate Board decision dated 26 June 2009, p 149

- ↑ W.P. No.24759 of 2006

- ↑ «Supreme Court rejects bid by Novartis to patent Glivec».

External links

[labot šo sadaļu | labot pirmkodu]Veidne:Extracellular chemotherapeutic agents Veidne:Piperazines

Category:Non-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors Category:Piperazines Category:Benzanilides Category:Pyrimidines Category:Pyridines